“Aleppo today is no longer a safe place, but it remains our home. And as the days go by, the longing for peace becomes a silent cry that we hope, one day, someone will hear.”

“Good afternoon, my name is Jacob. I’m writing to you from Aleppo, a city in northern Syria, constantly struck and devastated.” Jacob is a colleague who lives and works in Aleppo; this is the opening of one of the updates he sent us in recent days.

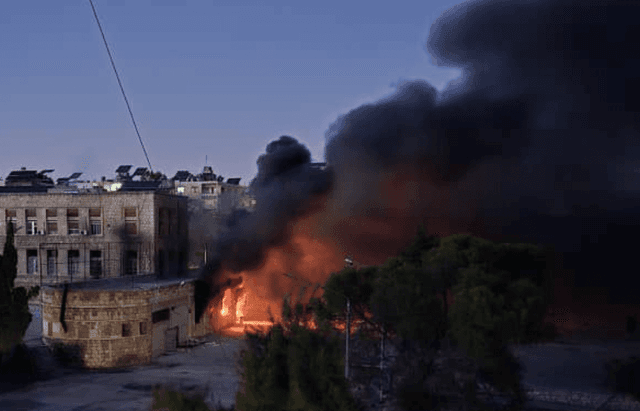

This is the reality for those who live in Aleppo: a battered, bleeding city, “constantly struck and devastated.” After thirteen years of war, fighting has once again cast a shadow of fear and uncertainty over the inhabitants. Anti-government jihadist militias from Hayat Tahrir al-Sham have seized control of the city and are expanding.

“Last Wednesday, we began hearing loud noises coming from the countryside,” recounts Anton Bardouk, the head of our office in Aleppo. “Mostly from the western part of Aleppo’s outskirts. Day by day, the sounds came closer: by Friday, we started hearing reports that the government was losing control of the city. Neighborhood by neighborhood, the government and the Syrian army were retreating.”

Giacomo Gentile, project coordinator for the Pro Terra Sancta Association, is currently in Syria on a trip planned to monitor ongoing activities. “I entered Syria on November 30, crossing from the Lebanese border on the route from Beirut to Damascus. Once we reached Damascus, the driver and I headed north toward Aleppo. But we quickly realized something was wrong. An enormous number of Syrian government tanks, along with some Russian ones, were moving from the south, from Damascus, toward the north.”

“At that moment, we understood something was happening and immediately diverted to the city of Latakia, where I stayed for two days,” Giacomo continues. “From our intermittent communication with colleagues and friends, we learned that Aleppo had been taken by militias linked to Tahrir al-Sham, along with Kurdish groups.”

“People began leaving Aleppo in a dramatic way,” says Anton. “Last Friday, I also left. It was total chaos. People were panicking. The road was packed with thousands of cars and people. It took us more than 18 hours to reach a Christian valley in the western countryside of Homs and take refuge there.” Anton vividly recalls the sea of cars and people clogging the road, all desperately seeking a way out: “I saw so many cars, so many people—police vehicles, fire trucks, and soldiers everywhere. It seemed like the government had completely evacuated the city.”

Even in Latakia, Giacomo witnessed the influx of displaced people pouring south to safety. “From Latakia, we started seeing many families fleeing Aleppo, their cars crammed with mattresses, suitcases, and blankets.” He was struck by the condition of those escaping: “There were dozens of open-back trucks, the kind usually used for carrying goods and materials, now overloaded with people—many children bundled in hooded jackets, hats, and blankets. They were traveling in desperation to escape Aleppo and find safer areas.”

“Now, food is needed.” Anton’s words are stark and urgent as he describes the looming threat of a food crisis for Aleppo and the thousands of displaced people. “There’s almost no bread, no fuel; there was no water for three days, and no one knows when it might run out again. Now the roads are closed; nothing and no one is entering or leaving Aleppo—no aid, no supplies, nothing.”

The bakery that Pro Terra Sancta and the Franciscan College operate in Aleppo is still running, for now. “I was there on Monday,” Jacob explains. “There are still large reserves of flour that allow us to keep going even during the road closures. It’s a blessing, as almost all public bakeries are shutting down for lack of raw materials. People can’t find bread and are scared.”

“The soup kitchen has also resumed its work,” adds Father Bahjat Karakach, a parish priest in Aleppo who has stayed to help his fellow citizens. “We are able to distribute more than a thousand hot meals a day, hoping to continue for as long as possible. Food prices have skyrocketed, and many people come to us for food because they cannot afford the little that remains.”

The soaring prices, the scarcity of food and money, and constant uncertainty have plunged Aleppo into chaos. “People are panicking, and nothing is clear. Here, in the Christian valley, many families are arriving without knowing where to stay, where to sleep,” Anton says. “Even one of our colleagues had to leave her home because it was near the city’s main square. When the square was hit by a missile, her house was also damaged.”

That colleague is Binan Kayali, a psychologist who works at the Franciscan Care Centre in Aleppo. “I had to abandon my home due to continuous shelling. Explosions shattered the glass, doors, and windows of all the houses in my area and damaged the Franciscan College of the Holy Land. I have now moved to Azizieh to be safer.”

“The reception centers, thank God, are still intact. This is thanks to the beneficiaries themselves,” Binan explains. “They protect the centers and regularly check on them. However, the mood among the population is dire: panic, fear, and anxiety dominate daily life. Many feel like prisoners, unable to leave their homes. They know that if they do, they might never return. Will to live is slowly fading, especially with the growing scarcity of food and basic necessities.”

The psychological toll is most profound on children: “They are experiencing a deep loss of normalcy: the deafening sounds of explosions, being confined indoors, and the lack of play are leaving visible scars. The other day, a missile landed nearby, and a six-year-old boy, seeing blood on the ground, began screaming: ‘I’m afraid of that blood! Whose is it? Are they dead?’ He cried desperately, trembling uncontrollably.”

Those who live in Aleppo, or who until last Wednesday called it home but now find themselves somewhere in the countryside between Damascus and Latakia, face daily, relentless questions. “The questions never stop,” Binan says. “‘When will this end? Where can we go?’ And the children keep asking: ‘When will we go back to school? When can we visit the park or Grandpa’s house?’”

“There are no answers,” Anton says sadly. “I asked a family here in the Christian valley why they chose this place and whether they plan to stay or go elsewhere. They told me, ‘We don’t know. We truly don’t know.’”

“Many,” adds Father Bahjat from Aleppo, “continue to ask themselves what the right thing to do is: stay or leave? ‘What if the battle reignites soon in the city?’ they wonder. ‘What if there are bombings targeting civilians?’ These are all valid questions, but no one can answer them right now.”

Binan leaves us with a phrase filled with sorrow and hope: “Aleppo is no longer a safe place, but it remains our home. And as the days go by, the longing for peace becomes a silent cry that we hope, one day, someone will hear.”

Today, Aleppo is consumed by uncertainty: the voices from the field are those of people enduring yet another moment of conflict, hunger, and despair, not knowing what will happen next.