1219, Damietta, Egypt: while the country burns with the fires and blood of the Crusades, two friars meet Malik al-Kāmil, Sultan of Egypt and Palestine.

The war, the fifth Crusader attempt to conquer Jerusalem, has also reached Egypt, with the strategic goal of capturing an important port to be used as a bargaining chip. In this context, Francis of Assisi—remembered today as the patron saint of Italy—boards a boat with the aim of speaking to the nephew of Saladin.

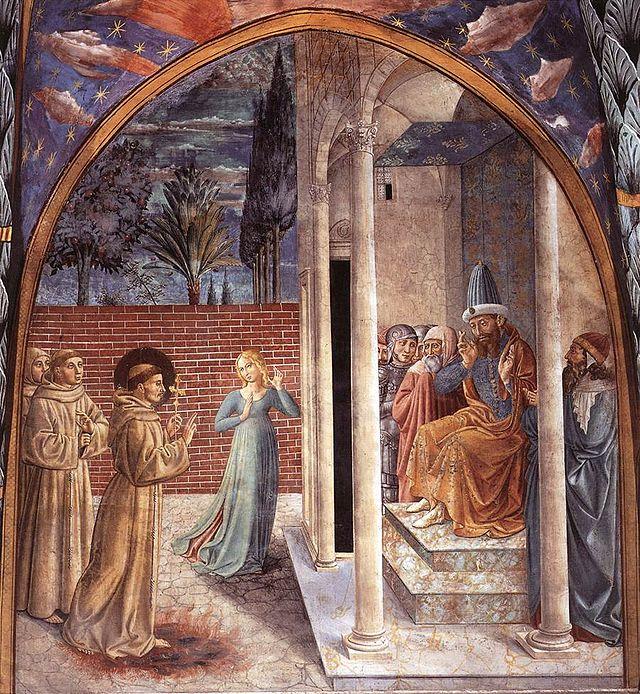

The encounter between Francis and the Sultan has become famous for its iconic and symbolic significance: “The Sultan and the Saint,” two worlds irreparably different and engaged in an endless conflict, meet in one of the magnificent rooms of the Sultan's palace to speak about faith.

The iconic power of this meeting has led to its being told in many ways, manipulated according to what different eras wanted to emphasize. For some, the dialogue between the two men became a fierce confrontation, filled with cruel tests of courage to prove the strength of their faith. A few centuries later, through the critical eyes of the Enlightenment, Francis was portrayed as a fanatic, in contrast to the wise and composed Sultan. Again, in colonial times, Francis’s expedition became a civilizing act, benefiting a godless savage people.

In more recent times, Francis's mission to Egypt has come to be seen as a symbol of dialogue and encounter. However, it is essential not to fall into oversimplification: Francis did not go to al-Kāmil to discuss cultural differences—he went to convince him that Christianity was the only true religion. Yet there is something revolutionary in this: the method Francis chose to achieve his goal was through words, advocating peace in the face of the Crusades’ weapons. In this sense, one can certainly see a symbol of dialogue: the friar approached the Sultan, who in turn received him.

In this light, we can glimpse behind the two men sitting opposite each other in the palace of Damietta, Francis’s rejection of the need to impose Christianity by force. The word is the alternative the saint proposes to the Crusades, an anthem to the possibility of sharing one’s thoughts and faith without shedding innocent blood. It is a reflection that remains highly relevant today, in a present where war continues to be a means of religious and cultural imposition.

The meeting between Francis and the Sultan marks a line that, updated and modified by the progress of history and culture, stretches through time to support the activities of our Association: behind each of our projects is the belief that we must not give up on seeking dialogue with the other, even when apparent differences seem to discourage the possibility of an encounter, even when violence and war, with their clamor, seem to drown out the possibility of a concrete alternative.

Indeed, at the time it took place, Francis’s gesture went completely unnoticed: among the smoke and cries of the Crusades, few noticed a battle fought with words, and those who did likely considered it the utopia of a madman. And yet, that gesture made history: once the violence of the war subsided, from the mists of time this encounter emerged, becoming a lasting symbol on which we continue to reflect.

This is also an important point for the mission and activities of Pro Terra Sancta: what we do today in the Holy Land, the projects we carry out to preserve and develop the cultural heritage of those who live there, and to protect their very survival, often seem so small in comparison to the complex violence engulfing the Middle East that they, too, appear like a utopia. What does it matter if Talia tells the children of Bethlehem the tales of their land? What does it matter if the School of the Roses can reopen, when everything around is burning? But often, peace starts from the ground up, the kind that eventually becomes political. It is from the words hastily exchanged between a friar and a Sultan that great cultural changes take root—those that, over time, truly change things and become History. Like in Damietta, more than 800 years ago.